Much has been made of how the writers behind the Game of Thrones adaptation enjoyed subverting audience expectations. They talked about it so frequently that it seemed to be not just an outgrowth of storytelling for them. Rather, it was a goal unto itself.

But is “subverting expectations” really what they did? I’d like to argue that the gripping plot twists that made the show so popular in its first seasons had a lot more to do with fulfilling expectations that subverting them.

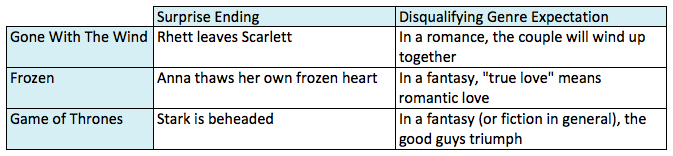

I’ll begin with Aristotle, who said that the best endings are “surprising, yet inevitable.” When Rhett leaves Scarlett sobbing on the stairs, when Anna’s sisterly sacrifice thaws her own frozen heart, when Scout Finch’s rescuer is revealed as the reclusive Boo Radley, we gasp in astonishment. But a moment later, the shock fades, and we find ourselves nodding slowly, muttering to ourselves, “Of course.”

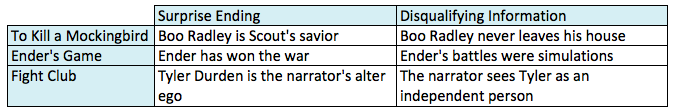

Let’s take a look at how those “surprising but inevitable” moments happen inside your brain. The “surprising” event is frequently something you would have disqualified as a potential ending when you first began reading. You probably disqualified it because of information you were given, or because of genre expectations.

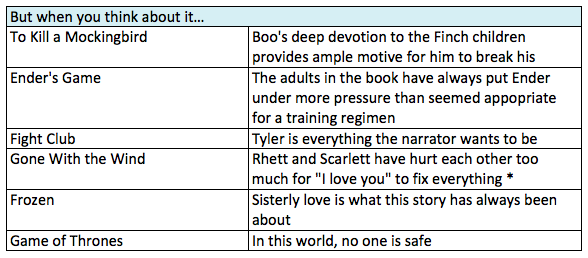

You’re shocked! But in the very next moments (assuming the writer has done his work right) your brain is latching onto little clues you’ve been given along the way. This is the “inevitable” part, and it happens suddenly, on an intuitive level—and then again, more slowly, as you think back over all of the clues and consider their import. If you’re watching The Sixth Sense, you’re suddenly realizing why Bruce Willis’s wife was so sad and distant. If you’re watching Fight Club, you’re thinking about the narrator’s contempt for himself, and how Tyler changed everything for him. If you’re watching Season 1 of Game of Thrones, you’re thinking about the deaths of Lady, Mycah, and Stark’s men, and about Bran’s fall from the tower. You realize no one in Westeros was ever safe—and you realize that you knew it long ago.

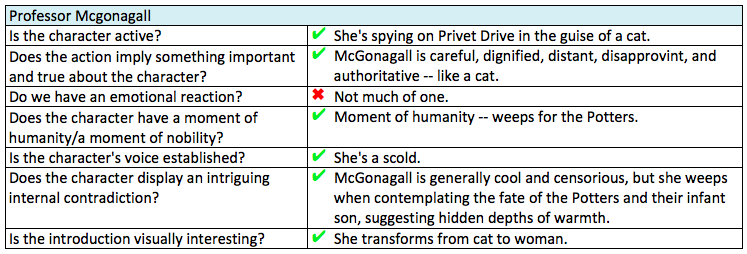

Note that most of the items on this chart don’t have a lot to do with practical clues: the initials on a handkerchief, the lock of hair clutched in a victim’s hand. They’re more emotional than that. They have to do with comprehending things like tone (Game of Thrones), theme (Frozen), character (To Kill a Mockingbird), or human nature (Gone With the Wind).

Game of Thrones subverted expectations exactly once: when they laid the network of clues throughout Season 1 that told us what kind of world we were really inhabiting. Stark’s beheading is not an example of subverting expectations; it’s an example of fullfilling the expectations we had internalized for this world without even knowing it.

When they did, eventually, subvert the expectations they had established—by, say, brining Jon Snow back to life after some hurried mumbo-jumbo, or having Jorah Mormont find the cure to grayscale in the very first place he looked, it was inevitably disappointing. In these cases, Game of Thrones subverted the expectations they’d established: that no one was safe, and that serious losses would not be reversed. No matter how much you liked Jon, these were among the least enjoyable moments of the series.

Subverting expectations sounds cool, but it doesn’t make much sense as a storytelling goal. If that’s your goal, you’ll wind up surprising people, but without that punch of inevitability that really satisfies an audience. It’ll be like the 1930 mystery novel The Door, which debuted the famous solution “the butler did it.” Surprising? Yes, because it defies genre expectations. Inevitable? Satisfying? Not so much.

A better goal is to control and selectively fulfill expectations by:

1. Either:

(a) Understanding the original set of expectations your reader brought into the story or

(b) Creating a set of false expectations based on information that turns out to be compromised (“Boo doesn’t leave the house”, “Ender’s battles were simulations”)

2. Creating a competing sense of expectations based on subtle, emotional clues you’ve woven into your narrative.

3. Fulfilling the second set of expectations.

* The TV show Friends went another way with a couple who had put each other through the wringer. The writers’ decision to paper over the decade of damage Ross and Rachel had done to one another with “I love you” was pleasing to longterm fans, but ultimately a little unsatisfying, because it didn’t feel inevitable in the slightest.